Improvising Dialog

Impro_ Improvisation and the Theatre

This is a snippet from my archives. I guess that it was written a little after the turn of the millennium because I know I was writing programs around then for anyone with the money to pay me, and I was bored as hell. In order to survive, I was writing large numbers of short stories, essays and blog entries, because as long as I was sitting at my terminal and typing the bosses thought that I was working.

It must be just me, but when I write, I use dialogue to convey information, but I was talking to someone today who told me, “Men report; women share.”

Like anything black-and-white about the sexes, it is obviously wrong, but it does say things about how people communicate. In my own fiction, my characters generally don’t share. In my life, I don’t like to chitchat, and I don’t initiate conversations. If no one talks to me first, I am not likely to talk to anyone. If I ask anything, it is to obtain information. If I answer anyone, it is to provide information. It is hard for me to imagine any other way. I am a reporter, not a sharer, but it may be that most people have other reasons for engaging in conversation.

Characters and most readers aren’t like me. Statistically, readers will skip paragraphs of exposition to get to the dialogue.

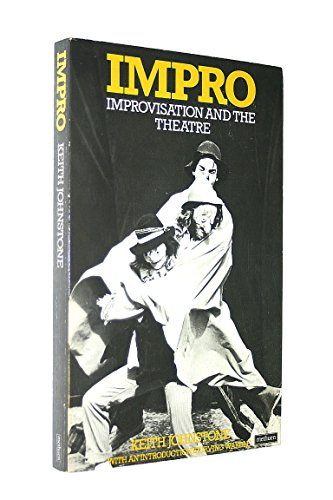

I have not thought much about this, but I recently read a book, on a friend’s recommendation, called Impro by Keith Johnstone. It is about improvisational theater, and it has examples and exercises for acting students to help them improvise. I have no intention of ever stepping on a stage, but I was told that I should read the book to improve the dialogue in my stories.

The book is excellent and has some very good ideas for creating dialogue. I have been thinking about the problem of dialogue for someone like me, who is a confirmed old reporter and never shares unless compelled to do so by his wife.

In fictional dialogues, there are several types of conversation. Each has a different goal and a different pattern. A writer would use these for stories as needed.

First is my main method: reporting or simple exchange of information. Here is an example between a star ship captain and his first officer:

“Captain, there is a ship approaching.”

“What kind of ship?”

“It is a class D Yerbian cruiser.”

“How far out is it?”

“49 light seconds, approaching fast.”

The captain asks questions, and the first officer answers them. Only in the last sentence does the first officer provide more information than is requested. In my mind, this conveys the immediacy and tension of the situation.

The problem is that it says nothing about the situation other than facts. The relationship of the captain to the first officer and their emotional state is not conveyed. If I were to add things like “he said with a tense voice,” it would be artificial and break up the flow of a tense situation.

This is an example of reporting. It is stark, quick and does nothing but convey information.

Is reporting bad dialog? Of course not. Is it boring dialog? I might be. Can it be improved? Yes, it can.

The first thing that might improve the dialogue is to include clues to emotional states. Here is the same dialogue with some emotionally charged words added to help add tension.

“Oh my God! Captain, there is a ship approaching fast.”

“I was afraid of that. What kind of ship?”

“It is a class D Yerbian cruiser from the death squad.”

“Those bastards found us? How far out is it?”

“Too close, sir; 49 light seconds.”

If the first example was too dry, then this is all wet. It is full of emotionally charged extra words that do convey a tense and emotionally charged situation, but I don’t think many people actually talk this way, and it comes off as overdone.

There are other things going on in conversations besides reporting and sharing. In any conversation, there is probably an element of status conflict. This is when there is a struggle to win a conversation, even when there is no evidence that there is an argument. The way it is described in Impro is that two people struggle to obtain status from a dialogue.

In the sample dialogue, there is a captain, who probably has status, and a first officer, who has less status. There should be an element of conflict as each tries to gain status.

“Captain, while you were busy, I discovered that there is a ship approaching.”

“I fully expected that we aren’t in the clear, yet. What kind of ship?”

“Not one that I would have expected; It is a class D Yerbian cruiser.”

“How long have you known about this? Is it getting close?”

“49 light seconds. If you had not been talking to the yeoman with the blue eyes, you would have known five minutes ago.”

The first officer who is resentful of the captain expresses this in each sentence. The captain, who does not like being spoken to like this, responds in kind. The dialogue is driven by personality differences, and although the information part of the conversation did not change, the subtext of conflict between the characters added to their development.

If the positions are reversed and the captain needs to struggle to keep a grain status, the dialogue might look like this:

“Captain, there is a ship approaching.”

“How long were you going to keep that to yourself? What kind of ship?”

“It is a class D Yerbian cruiser.”

“I can see that from here. How far out is it?”

“49 light seconds, approaching fast.”

The captain abuses the first officer to show his higher status, and the first officer just takes it.

Another thing that adds to dialogue is an element of persuasion or seduction. This can be a simple debate or a full-out argument. It can be flirtation or bullying. The object is for one character to change the mind of another. The basic element of personality is that it is changeable, so a dialogue that alters a person’s viewpoint, opinion or preconception is powerful stuff in fiction.

“Captain, there is a ship approaching.”

“That’s impossible; we left the Yerbians back in the Gamma cluster; they couldn’t have found us so quickly.”

“The instruments don’t lie. It is a class D Yerbian cruiser.”

“I can’t believe it. Check the calibration.”

“I checked them twice. It is 49 light seconds out, approaching fast.”

“Oh my God, we are done for!”

The first officer has to convince the captain that there is indeed a ship out there. The information is wrapped in persuasion. I added the last line to show that the captain had come to a change of mind by the end of the conversation. This makes the dialogue a little stronger, even if it is way over-the-top.

The book, Repo, has many more examples, but I’ll leave you with a silly kind of comedy dialog.

Sometimes people just like to hear themselves talk. There is no pretense of having a conversation, and people babble on, leading to comic results. There is an old comedy skit that starts off “Is this Thursday?” and each person just says something totally unrelated to the previous line, except for some small piece to connect the dialogue. For instance

, the next line might be, “I have to see my Aunt Emily on Thursday.” Followed by “I knew a girl named Emily, but she wouldn’t let me kiss her.” — “I wouldn’t let my brother kiss me” and so on.

You can do this kind of thing with the captain and the first officer, but it won’t get you to what to do about the Yerbian threat.

“The Yerbians are 49 light seconds out and coming fast.”

“I once danced with a girl for almost 30 seconds before she slapped me.”

“If you don’t start thinking about that girl, you’ll get us killed.”

“I was thinking that I should get some additional life insurance, just the other day.”

You can continue along this line of analysis ad absurdum, but there are many other scenarios that will help you write dialogue, I recommend the book.

The book is Keith Johnstone-Impro_Improvisation and the Theatre, is in the public domain and is a free download from archive.org.